Shelter Get help

How we made it easier to get help from Shelter and experimented with a new emergency helpline.

UX Lead — 2017

The problem

Shelter’s helpline and face to face services didn’t have enough capacity to help everyone that needed their support

We formed a very small team to look at the question: how can we better use Shelter’s limited resources to do a better job of helping users in need?

What we learnt

We didn’t have a user researcher, so I worked with another designer and a product manager to conduct user research. A highlight was travelling to Sheffield to shadow helpline advisors as they were doing their work and talking to people seeking help.

We found that, as housing issues and personal circumstances get more complex, users are less capable to resolve their housing situations on their own. Issues tend to be interlinked, so it can be difficult for users to verbalise what their problems are. Often, the issue they present as key when contacting us is only part of the real problem.

We also learnt that many users feel the need to talk person to person when:

- they feel vulnerable or emotional

- perceive the situation as urgen

- have to deal with very complex situations

While most users generally feel confident using a website, their confidence and capability is reduced when they are in difficult circumstances.

On top of all that, people can feel out of their depth when they are not familiar with the technical and legal worlds of housing and homelessness. Local authorities and other organisations often don’t speak plain language, making things even harder for people in an already stressful situation.

When we listened to Helpline calls, we learnt it wasn’t uncommon for advisors to spend over twenty minutes talking to someone who had a simple dispute about their tenancy deposi but was in a safe and stable situation otherwise. That was despite the helpline being oversubscribed, and the fact that lots of other users with more urgent problems couldn't get through.

What we did

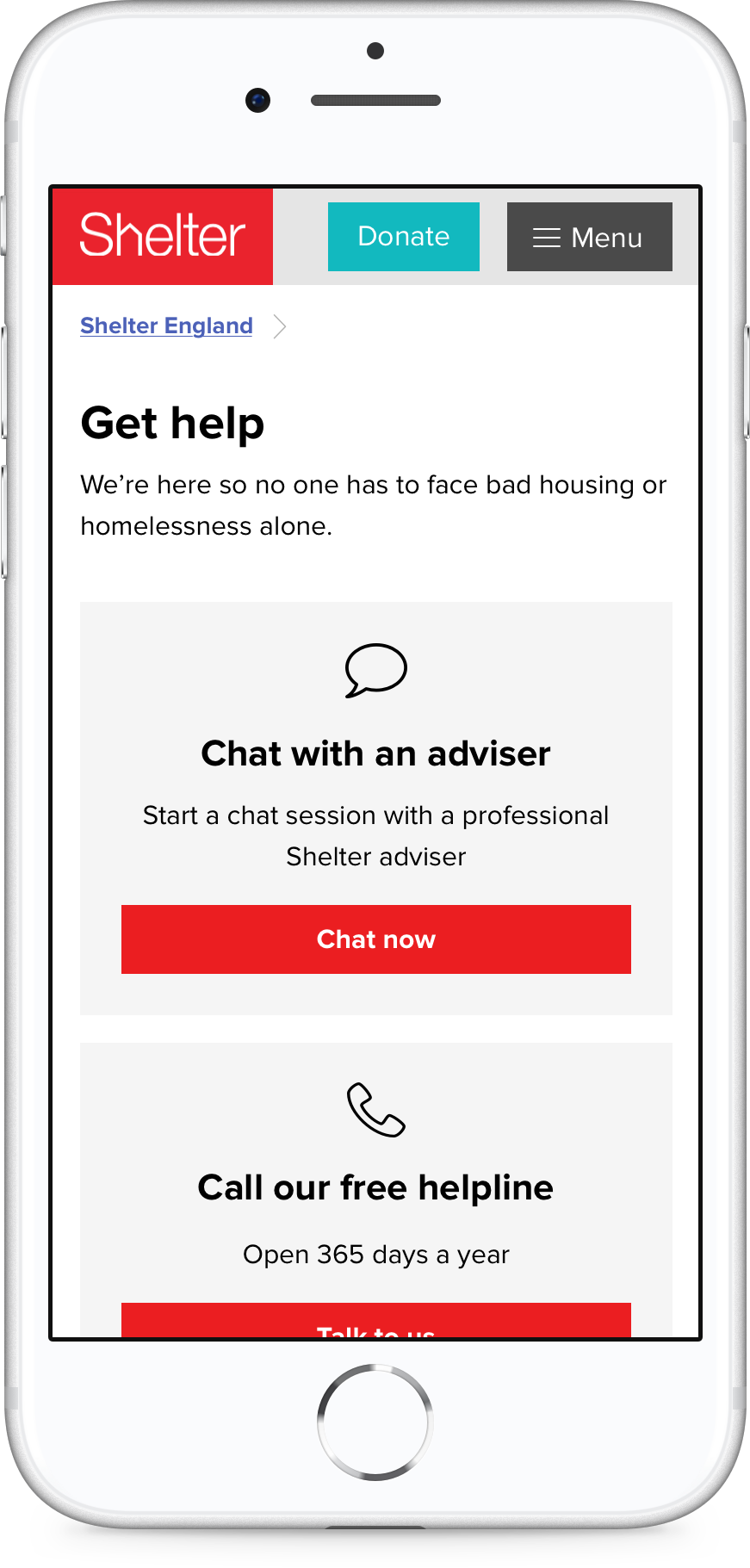

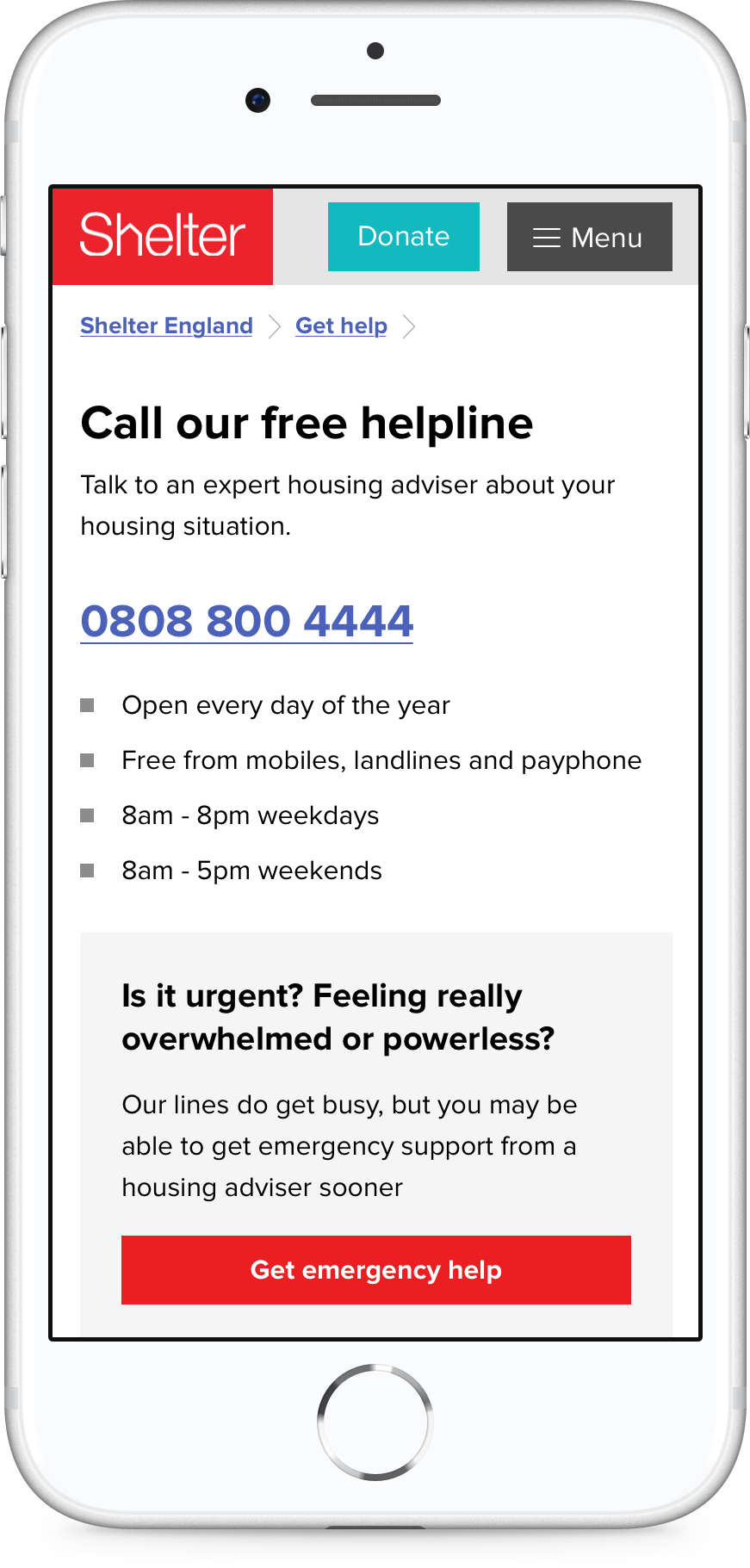

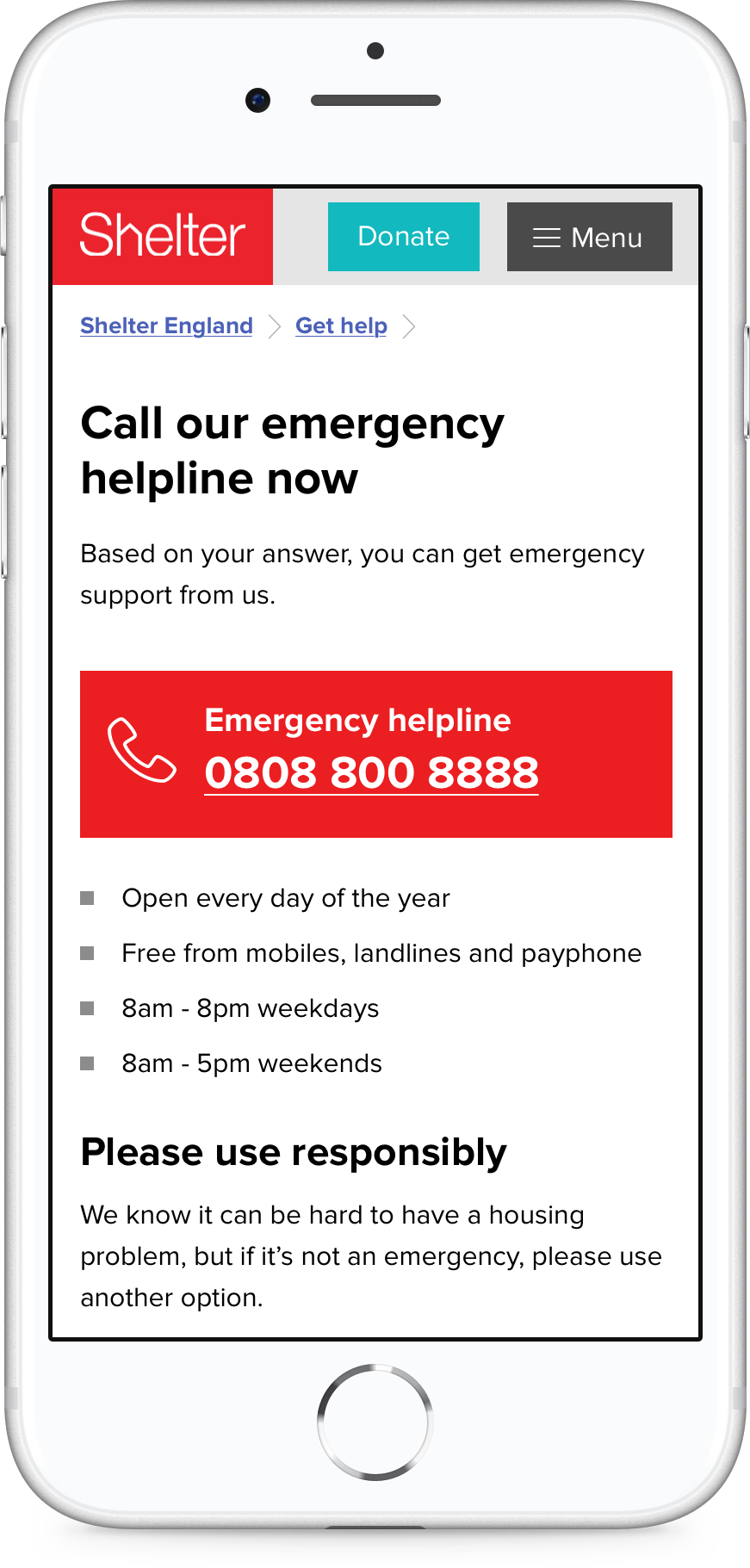

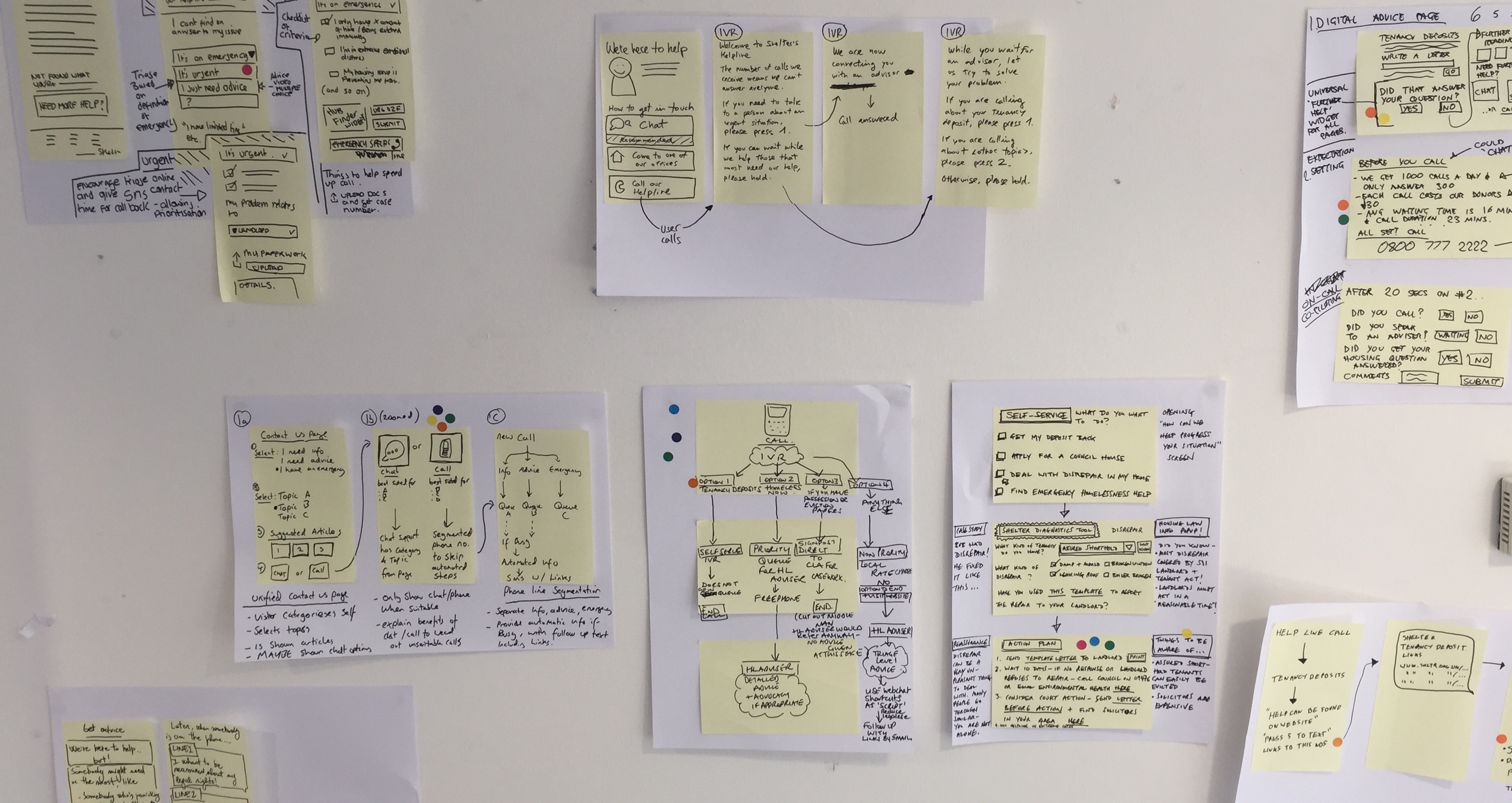

After quickly exploring a range of directions, we decided to start by focusing on helping more of those users that need us urgently. We converged on a prototype for an Emergency helpline, that would give those in emergency situations priority over the rest of users.

We quickly designed and built a small flow. At the same time, we worked with the telephony team in Sheffield to set up a second phone number for the emergency line and run it as an experiment. For a week, helpline advisors would receive calls from two separate lines, and we’d see initial results for a new emergency helpline.

Results

In just 6 weeks of work, from initial research to running the experiment, we saw very encouraging results. We made a significant step towards making things better for our users in a rapid and iterative way.

As an organisation, Shelter was new to this approach. Stakeholders were often used to long cycles of work and too many meetings. This experiment got us a lot of buy-in to continue growing more user-centred approaches.

54% of urgent calls got through and talked to an advisor

Up from 20% with the previous operating model

38% of users we helped were feeling really overwhelmed

Before, they wouldn’t have qualified for priority support

Got funding for a dedicated cross-functional team

Shelter funded a permanent team to continue with this work