NHS service manual

How we ran user research and design workshops to push back on initial assumptions and start in the right direction.

Senior Interaction Designer — 2018

The challenge

In 2018 the NHS was growing its user-centered community. As the number of teams doing good work grew, they tried to create shared resources. But without anyone dedicated to updating and maintaining these resources, they went out of date.

As a result, teams ended up figuring things out on their own, which slowed them down. Even more importantly, it was hard to share knowledge with others. And there were also inconsistencies for users visiting different parts of the NHS.

Discovery

Before we started, teams had collected a wishlist with all the things they’d like to see built or documented. But before we started, we wanted to dig deeper into people’s experiences to really understand their context and be able to focus our work on their real needs. At first, we didn’t have a dedicated researcher. Working with the content designer in the team, we decided to plan and conduct the research ourselves.

We recruited 50 participants. We had a mix of roles (developers, product, design, etc), projects and levels of experience. We were lucky that recruiting people within the community was easy. We managed to do all the interviews in just two weeks.

We found that:

- people across the NHS were contributing to critiques and Slack threads, which was positive

- there was a strong desire for better shared resources and ways of working

- but people didn’t know where to find guidance

- teams used very different approaches and found their own ways of doing things

- there was an old frontend library, but it was not being maintained

- designers were sharing their personal design files with others, but there wasn’t a central library

Most people expected to have good standards for design, development and agile ways of working. They wanted to have more consistency, but keeping flexibility to do what’s right for each them.

Most users believed this would save them time and it would give them clearer boundaries. Something we heard a lot was that "it would help them push back" against unreasonable requests from stakeholders.

Just build this

As we finished our research, we had an unusual meeting. Someone senior had some ideas that they thought should go in the first version of the manual. Their reasoning was that it was an existing resource and that it would allow us to launch a first version very quick.

Now, while I’m all up for rapid development and iteration based on real use, this request just didn’t fit with what we found when we talked to users. It was also derailing our existing plan, and it took me by surprise.

I argued against it, even if it made the meeting uncomfortable. But they had made their mind, so it was a tricky situation. I suggested that rather than jumping to building their request, I could organise a set workshops so that we could all align on the problem and make sure we were on the same page. It would only take a few days, and at the end of it we’d have a prototype to test with users.

Having used this approach over the years, I was completely convinced it was the right thing to do, and I knew we’d still have time to build and deliver on time. Happily, they accepted. But there was a pretty big amount of pressure to make sure the process would get us where we needed to.

Design sprint

Like many others, over the last few years I’ve ran a set of workshops that draws inspiration from the Google Ventures design sprint. It’s the same principles, a similar structure, and quite a few of the same activities. But I add, remove and tweak things as I see fit.

(As a quick side-note, it’s become quite popular to argue about whether design sprints are overused or how they are not a solution to all problems. I don't find these that useful. From my perspective, use what makes sense and change things to make them work in your own context).

So we managed to find a nice space in Leeds despite having no budget for it. We did tons of preparation to make sure everything was smooth and we ran on time. We’d spend three days with a group of 9 people, so we needed to make sure it was worth the effort.

Soon after starting the first day, it was clear one of the participants wasn’t very keen. They were set on what they thought we should be building, and so they felt like it was a waste of time. Fortunately, everyone else was up for it. As we made progress, the skeptic started to understand the value of what we were doing. By the end of it, they were even enjoying it.

We started by agreeing our goal: to help teams efficiently produce high-quality, consistent NHS services that meet people’s needs.

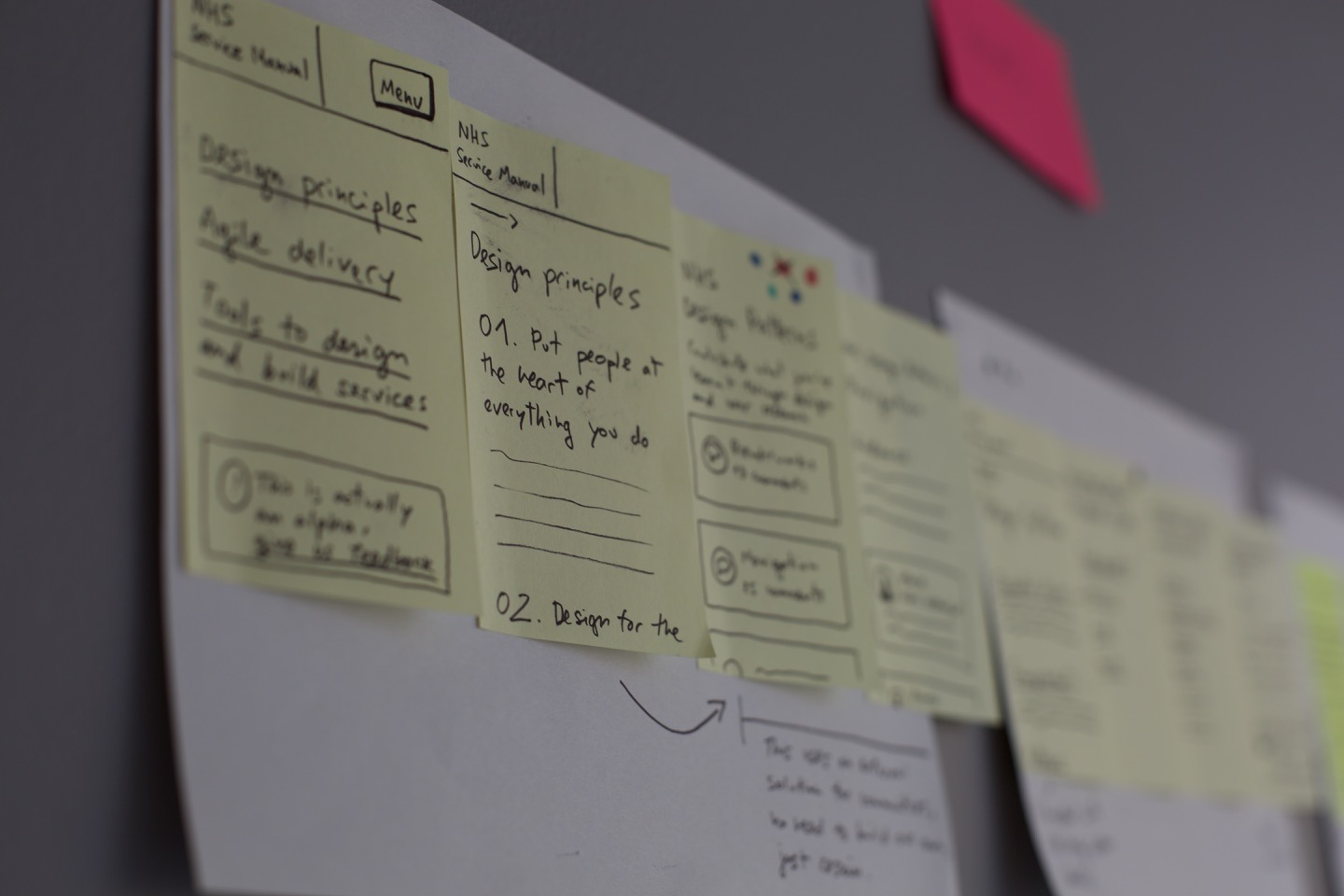

We reviewed the user research, a journey map I made, as well as other context: from technical issues to measuring success.

We agreed that the areas we wanted to address first were:

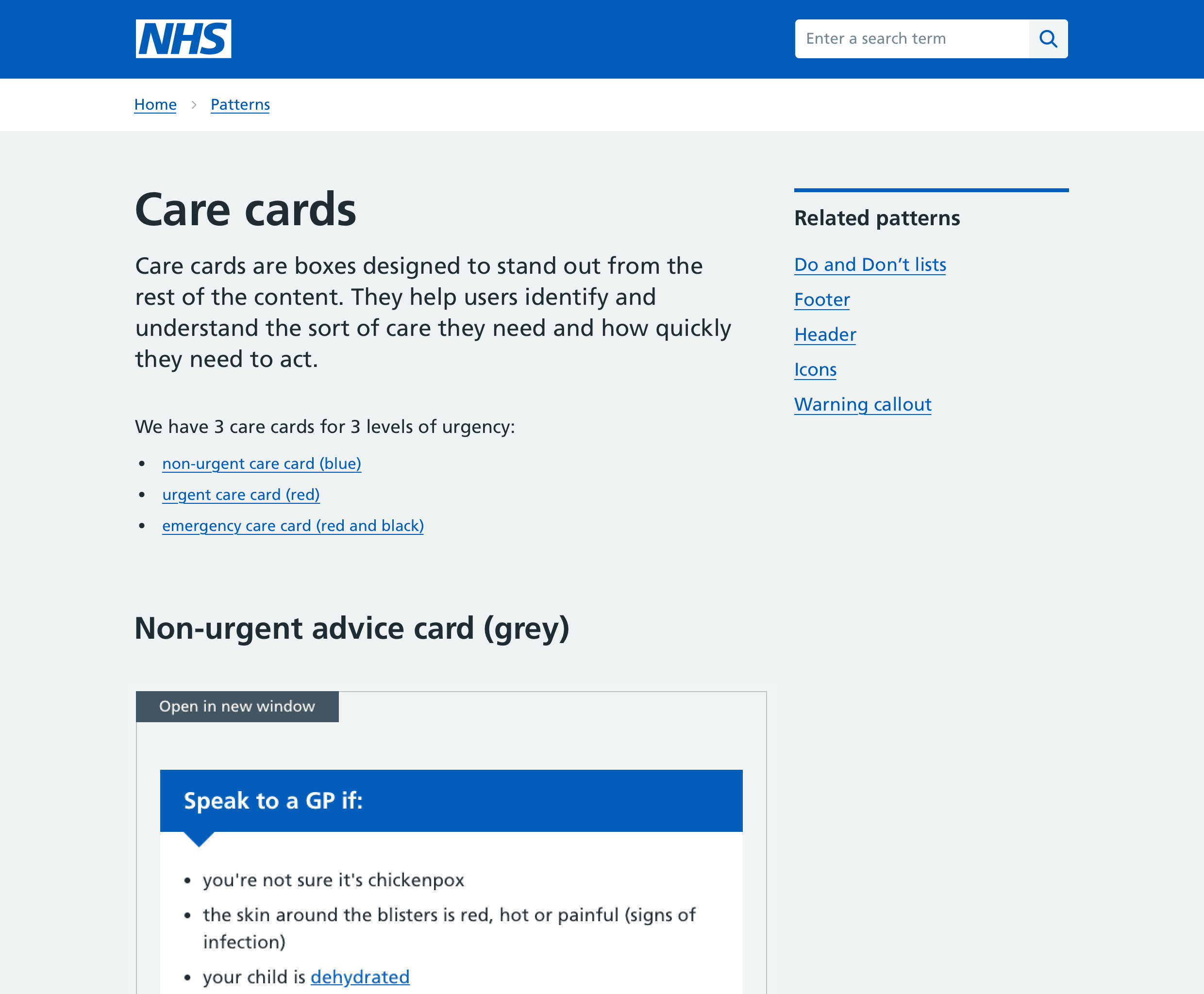

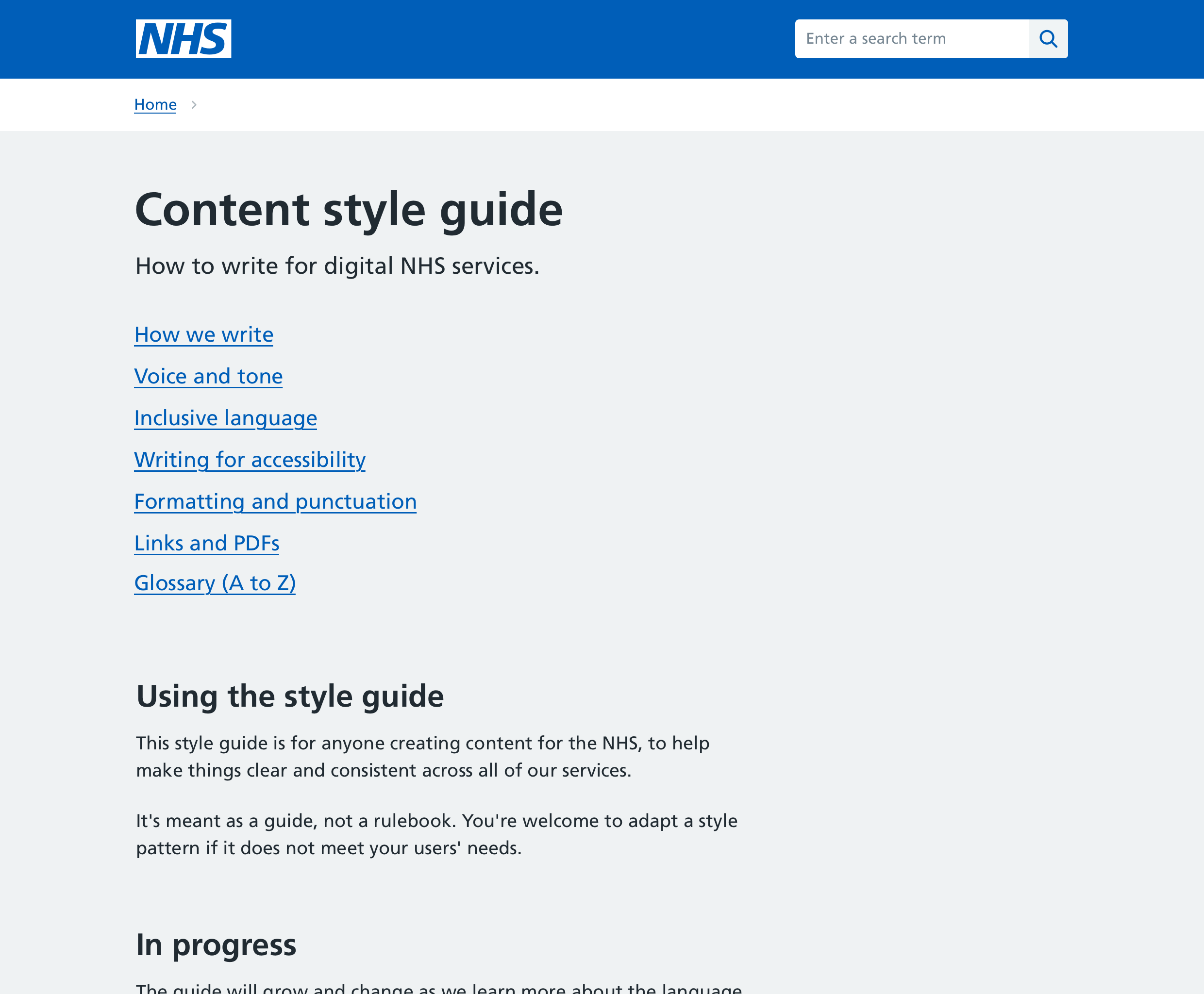

- a design system with useful, up-to-date patterns for designers, front-end developers and content people

- covering ways of working, drawing from the Government Digital Service, but also defining areas of difference

- exploring the set of criteria healthcare services need to meet, and how they may be assessed

We sketched a wide range of ideas, then converged on the ones that had most potential

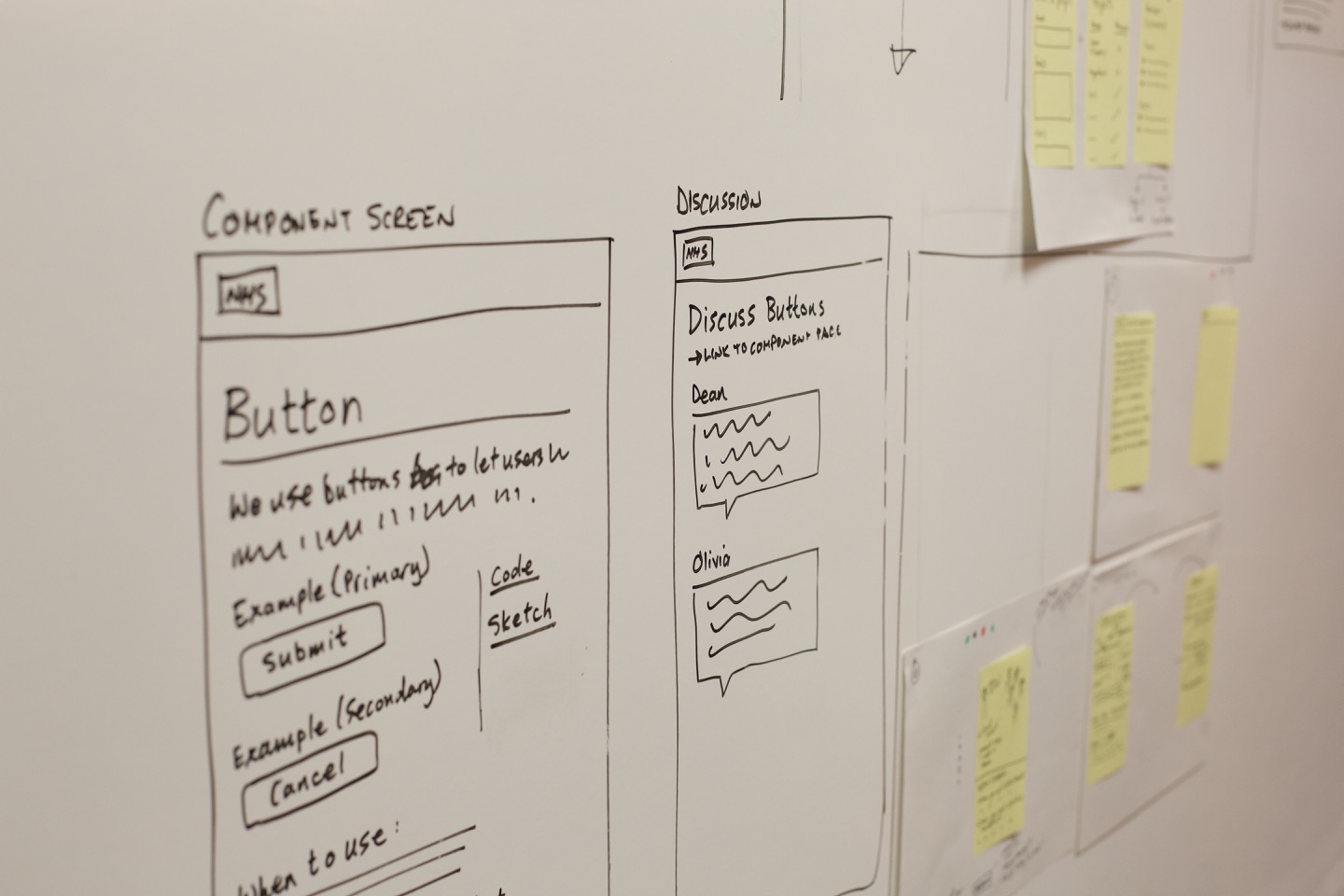

After the three days of workshops, I spent a day making a quick, low-fidelity prototype that we immediately tested with users.

When we tested the prototype, we found that:

- people really wanted shared styles, components and patterns, as soon as possible

- most people said they wanted to be involved and contribute, rather than being fed from above

- but the stuff around assessing needed more work

Building, launching and iteration

Over the following months, we launched a first version, iterated it, and introduced new sections.

Results

The service manual and the community we created around it has received excellent feedback. It’s now a central tool for dozens of teams designing and building NHS services.

In the summer of 2019 I moved teams to work on Find a GP. The rest of the team continued to do great work, iterating and improving the manual further.

It has been nice to see community we set up has continued to grow, be active, and shared practices during the COVID-19 crisis.